The Anatomy of Melancholy

This is one of those books that is unique, not necessarily in its subject matter, but in its execution thereof. At face value, the Anatomy of Melancholy was written in first 1621 by the Englishman Robert Burton (the author at the time took the pseudonym "Democritis Junior") and is an exhaustive treatise on the subject of melancholy as understood in 17th century Europe. He then released a number of follow-up editions during his lifetime, the last being in 1653. Just beneath the surface, however, is a treasure trove of quotes, anecdotes, and one of the funniest satirical introductions in literature.

The book has been lauded by every one from contemporaries (Samuel Johnson), Victorians (John Keats, Washington Irving, Laurence Stern, & Charles Lamb), early 20th century writers (O. Henry among them), to modern day writers (Phillip Pullman, Jorge Luis Borges, William Gass) and more. I originally learned of the book through Borges where the quote below precedes the short story The Library of Babel.

By this art you may contemplate the variations of the 23 letters...

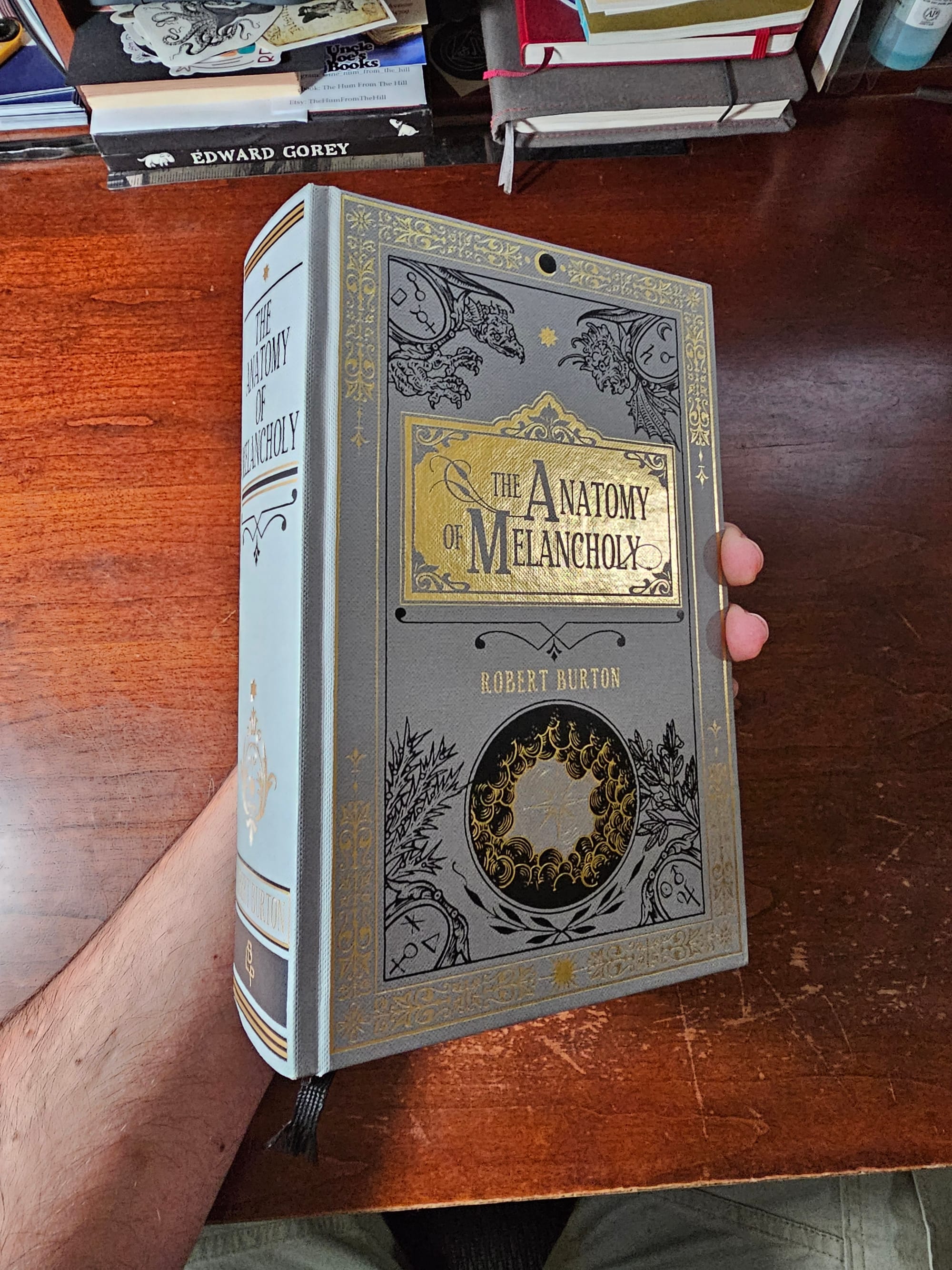

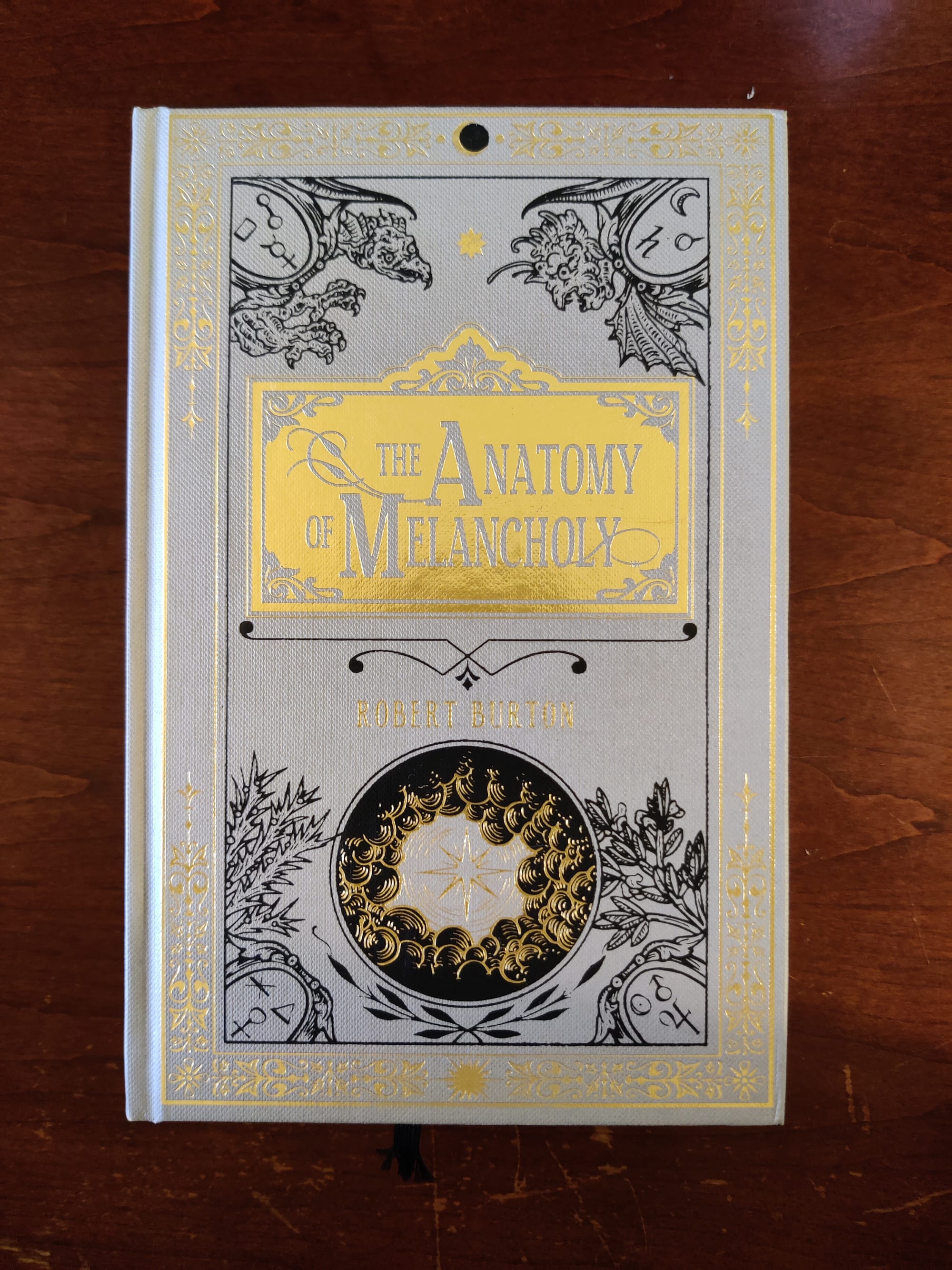

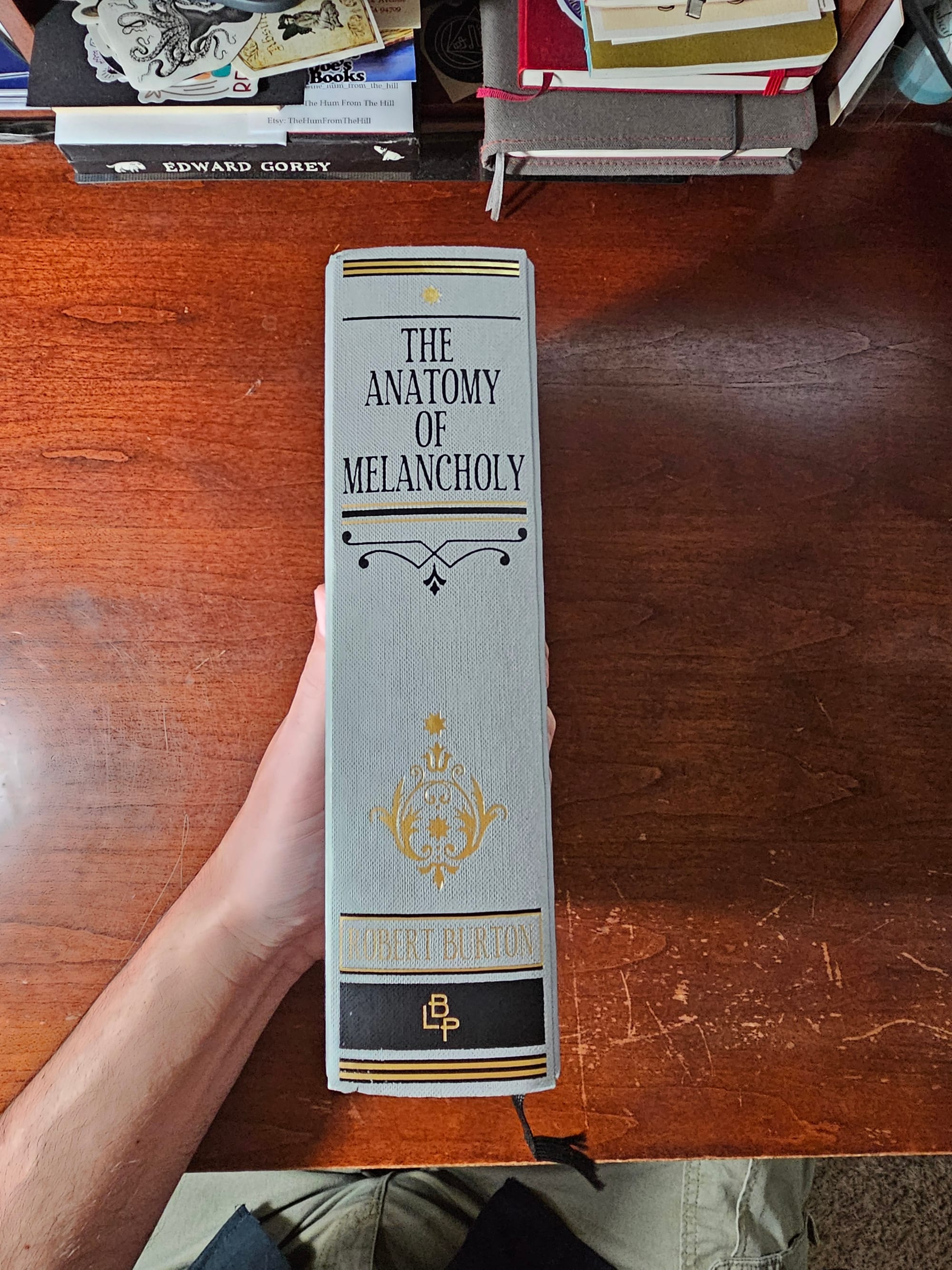

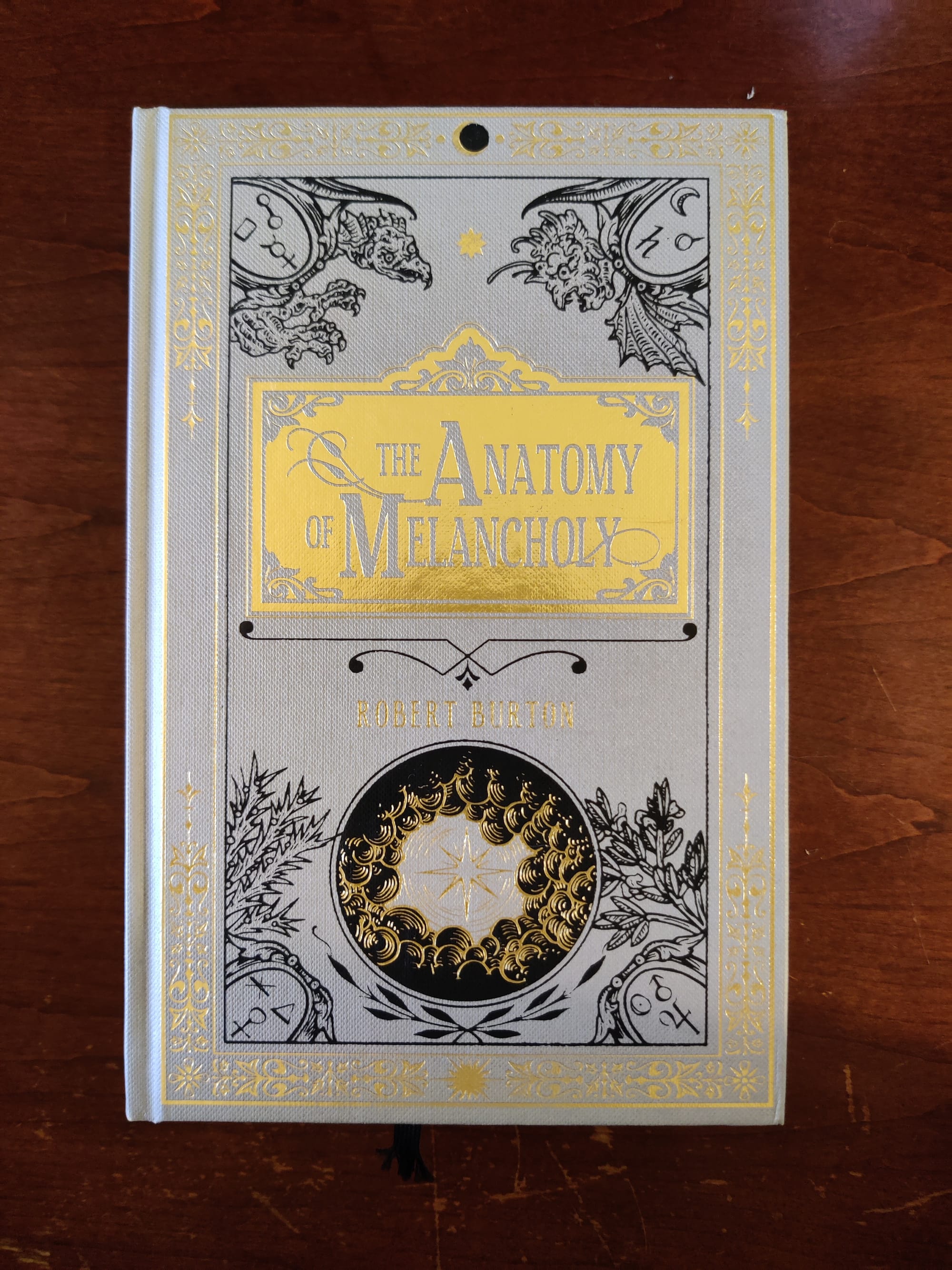

The only copy of Anatomy that I have is a cloth-bound hardback from Black Letter Press, a small independent publisher out of Germany that specialize in fine reprints of classical and occult texts. This may change at any point, however, as I am always searching for affordable editions of the book online. Especially of interest to me are the three-volume leather bound copies that were printed when the book saw a resurgence of popularity in the late 19th century, and the more recent annotated editions.

The book itself is beautifully bound in a grey geltex cloth and has wood-free 115g cream paper. The front cover and spine are both gilded in a classical design that is quite decorative. This edition is an omnibus version of what was originally a three, or six, volume text. The only downside to this edition as I see it is the lack of footnotes that are present in many other modern reprints, no doubt due to copyright issues. But that aside it is a joy to flip through and read on a rainy day... or any day for that matter.

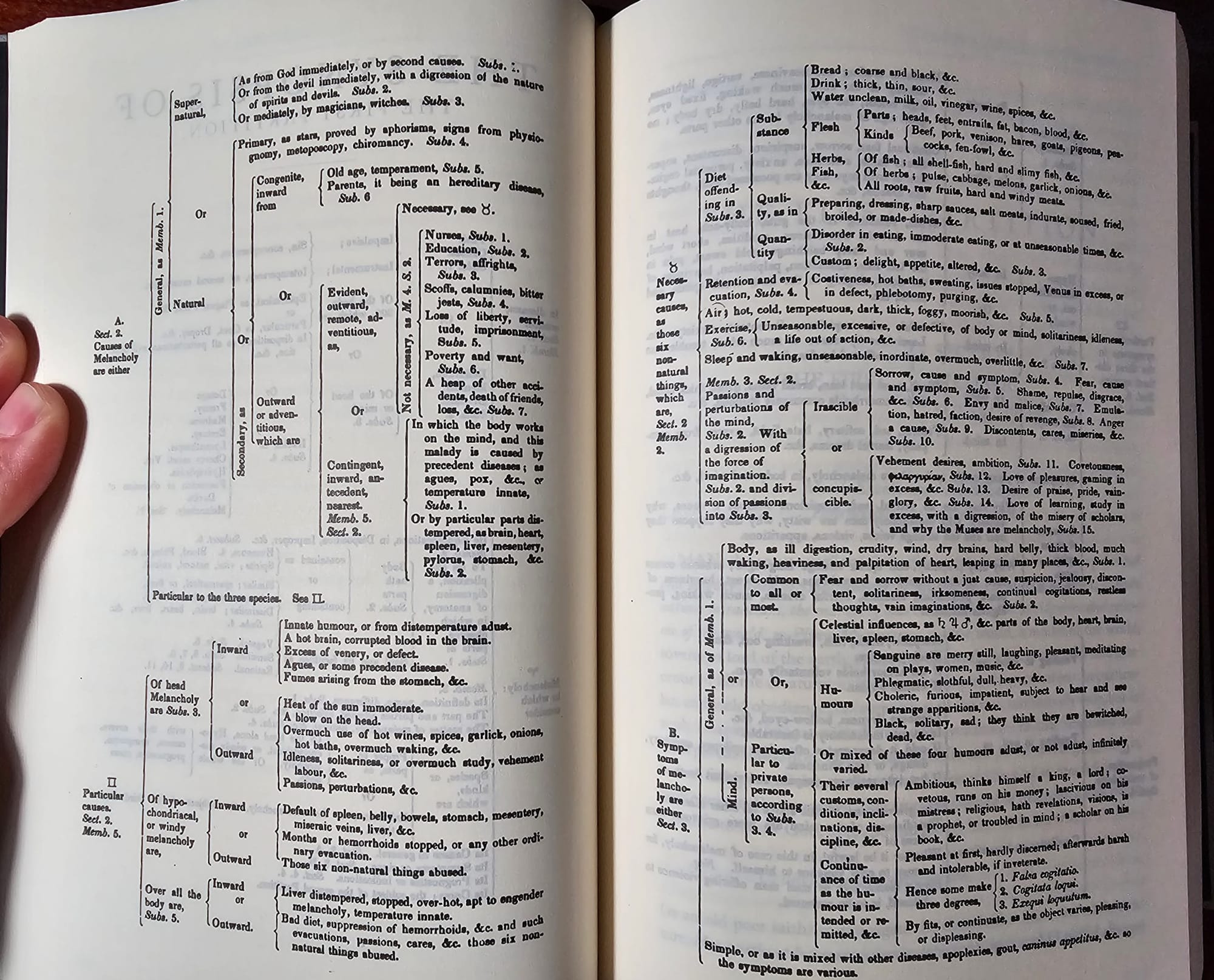

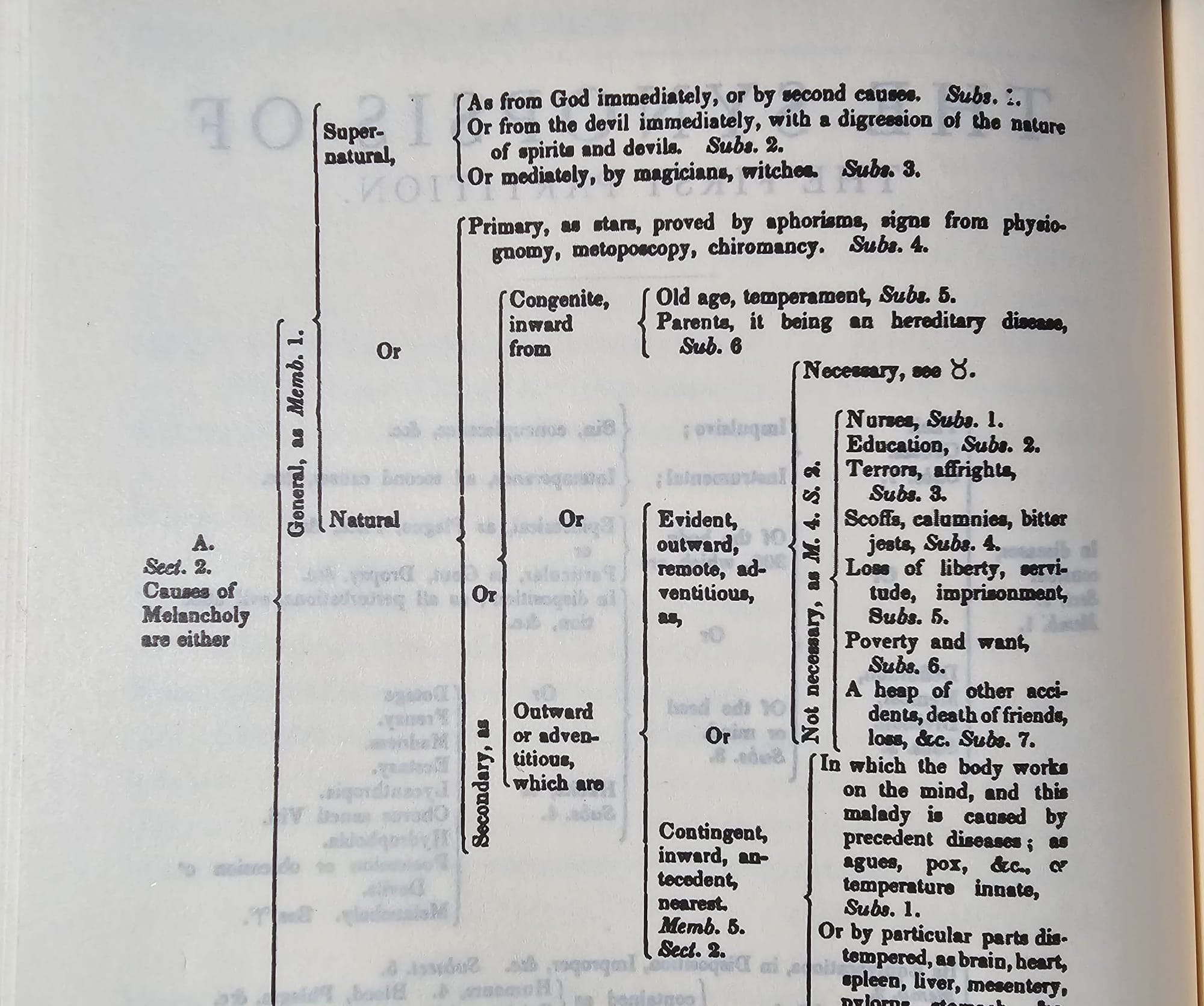

One item of particular note for any edition of Anatomy is the structure of the Synopsis, as a sort of proto-table of contents. I've not encountered a similar thing in other books, although I'm certain it existed elsewhere, and it does make finding particular topics a bit of a chore within. Although, I imagine it is slightly better when you are dealing with a multi-volume set instead of an omnibus edition as this is, but that is conjecture and won't really know for certain until I can get my hands on one.

One of the most amazing things of this book is that you don't need to search for anything, you can just open it to a page and start reading. You might land on an entry on why the planet Mercury is a possible cause of misery to scholars and students, or how your friends and family can help to lift a melancholic up from heartache, or a section on clarity in honesty where Burton is referencing everyone from Sarpedon, Glaucus, Homer, the Latin Vulgate all interspersed with a running commentary that links them all.

And it is this last point that first drew me into The Anatomy of Melancholy. Within its covers you find just about every person that had written a book available in the 17th century. Burton must have been unbelievably well-read to have been able to pull the quotes and anecdotes he uses from thin air and put them on paper. And as a perennially fledgling Latin student, every page is filled with Latin. Some of it is translated, but most of it is not. Every page is a potential treasure-trove that leads you to some other heretofore unknown writer in medieval Europe. The following quote, for example, is from the beginning of the satirical introduction and is a decent, if brief by Burton's standards, of the style.

"...every man hath liberty to write, but few ability. Heretofore learning was graced by judicious scholars, but now noble sciences are vilified by base and illiterate scribblers, that either write for vain-glory, need, to get money, or as parasites to flatter and collogue with great men, they put out burras, quisquiliasque ineptiasque [nonsense, rubbish, and triffles]. Amongst so many thousand authors you shall scarce find one, by reading of whom you shall be any whit better, but rather much worse, quibus inficitur potius quam perficitur, by which he is rather infected than any way perfected."